The balance wheel pivots are the thinnest in the watch, as they are the lowest torque. However they also carry what is often the heaviest wheel and so therefore are very vulnerable to break if the watch receives a shock. For pocket watches and clocks this was not a huge problem as they were generally kept safe, but a watch worn on the wrist spends most of its day on the move.

The First Watch Anti Shock System

In 1790 Abraham-Louis Breguet invented the Para-chute device which was a spring which helped to absorb any shock to the balance pivots and keep it from breaking.

Modern Watch Anti-Shock Setting

The modern day shock spring is based on the same principle; however it was not until the 1950s that the anti-shock system became widespread. Before this a broken balance staff was one of the most common fatal problems a watch would face.

Nowadays the shock system is so successful that a balance staff is rarely broken, and most damage can be traced to direct interference from someone who has opened the watch. This has led to current balance staffs actually being of a lower quality than those made 30+ years ago, with even the top tier watch houses choosing to chemically burnish the pivots with acid to save costs rather than burnishing them by hand as in years gone by.

Burnishing is where you rub a surface of metal smooth, compacting and hardening it in the process. All pivots are burnished to reduce wear, and as a result do not bend out of shape but shatter when force is applied

Modern day shock systems also help reduce the friction on the pivots, reduce contamination and oxidisation of the oil and ensure that the pivots are always centred.

The oil sink with a shock setting is usually reserved for the balance wheel pivots; both top and bottom, although on some higher end watches it is used elsewhere, specifically on the escape wheel.

The Anatomy of the Watch Anti-Shock System

As with most things in horology, everything has many names:

- The Setting can be called the Anti-shock Setting or just the Block

- The Chaton is sometimes known as the Free Setting

- The Balance Staff Jewel can be the Pivot Jewel

- The Cap Stone is often referred to as the Cap Jewel or End Stone

- And the Anti-Shock Spring could be the Shock Spring, or referred to by its brand name such as Incabloc

Function of the Parts in an Anti-Shock System

Anti-Shock Spring

The spring is usually made out of brass, or a similar metal with elastic properties. It needs to be strong enough to absorb any shock and then return the Cap Stone and Chaton back into place

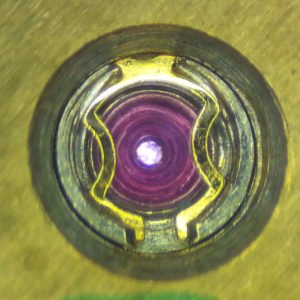

Cap Stone

The Cap Stone is made out of synthetic ruby (aluminum oxide). It is curved at the top and flat on the bottom with a highly polished surface. It is immediately recognisable as it does not have a pivot hole in it. This holds the oil in place and in most modern watches is coated in a material (usually Fixadrop/Epilame) to prevent the oil spreading. It sits on top of the Chaton and is held in place by the Anti-Shock Spring and also to the Balance Staff Jewel through the capillary action of the oil

Balance Staff Jewel and Chaton

In almost all cases the pivot jewel will be friction fitted into the Chaton. Together they sit loose in the Setting, and are held down by the Anti-Shock Spring

Setting

The Setting is fixed to either the mainplate of the watch or the balance cock depending on whether it is the top or bottom Setting. It has the lock system that the Anti-Shock Spring uses to hold itself in place. It is shaped so that the Chaton will want to return to the centre when pushed down by the spring in normal conditions after a shock.

Types of Anti-Shock Spring

There are currently two main companies that make shock settings; Incabloc and Kif. Of these the most common setting in use is the Incabloc, mainly due to its use in ETA movements.

The shock systems can be split into two main groups, those that are fixed in place and hinge upwards, and those that are removable.

Removable:

- Kif-1

- Kif-2

- Novodiac (made by Incabloc)

- Paraflex (made by Rolex)

- Etachoc (made by ETA)

- Duofix (made by Rolex)

Hinged:

- Incabloc

- Kif-3

- Kif-4

- Kif-6

Incabloc is an independent company and Kif is part of the Acrotec group. There is a story that Paraflex was formed due to an argument Rolex had with ETA (now part of the Swatch Group), and so they decided to make their own “superior” shock system as a result.

The Evolution of the Watch Anti Shock System

To understand the need for the shock setting let’s take a look at how it evolved, and then we’ll take a look at how they work.

How an Anti-Shock System Works

The Chaton sits loose in the Setting, with the Balance Staff Jewel friction fitted into the Chaton and the Cap Stone sitting on top of the Chaton. The Anti-Shock Spring applies a downwards force on the Chaton and Cap Stone, holding it in place.

If a shock is received then the balance staff will push its shoulder against the Chaton and it will move both the Chaton and Cap Jewel with the Anti-Shock Spring flexing to allow this limited movement. This small movement absorbs the force of the impact in a safe way, thereby protecting the vulnerable balance staff pivot.

Once the shock has been absorbed, the spring’s elastic properties will mean it will want to return to its original shape and by doing so will push the Chaton and Cap Stone back downwards. The Chaton and Setting are shaped so that this downwards movement will guide the Chaton back towards its natural central position.

The educational website clockwatch.de has a wonderful Flash animation where you can apply a shock and watch how the Anti-Shock System works. You can follow this link: https://www.clockwatch.de/index.html?html/tec/sto/inc.htm

Examples of Anti-Shock Systems and How to Remove them

Glyn

3 August, 2013 at 10:40 pm

Thanks for a great and very clear article. Just discovered your website today. All good stuff.

Best of success in your career….

All the best

Colin

4 August, 2013 at 2:26 pm

Hey Glyn,

Thanks a lot, I really appreciate your encouraging comments!

Don't exercise with an mechanical? (How my Seiko 5 gained 20sec in 40 minutes) - Page 8

5 November, 2013 at 8:21 am

[…] Watch Anti-Shock Settings | Great British Watch Company has a comprehensive page on shock protection mechanisms and their evolution. […]

Wayne

2 January, 2014 at 5:55 am

Congratulations on your watchmakers quest! I found your site today and have been reading it most of the evening. I really enjoyed your concise and informative presentations. I look forward to following your work and have subscribed for update notifications.

You have really put into perspective what an undertaking it is to become a watchmaker. Although I hate to be just a hack, I may need to reevaluate my recent obsession with these tiny devices, and be satisfied with simple tinkering. It seems that it is a bit late for me to chase a formal education in this field. I am glad that you are. Sincere Regards.

Colin

5 January, 2014 at 3:25 am

Hi Wayne, thanks for your kind comments! If you want to move beyond the basic tinkering then, yes, watchmaking can be quite daunting and will require a lot of effort in learning. I wouldn’t be put off by age though, I was 32 when I decided to change my career, and a lot of the most repsected horologists only took the field up after their retirement. One of the main attractions of watchmaking is that it is a career that is not resticted by age. Provided your hands and eyes remain healthy then you can literally keep it up as a past-time, whether professionally or as a hobby, until you drop. Cheers

Anyone notice the Shock absorbers has changed? also the strap - Page 2

20 January, 2014 at 1:47 pm

[…] can correct me if I'm wrong on that one!) I liked this link when I read up on it a while ago: Watch Anti-Shock Settings | Great British Watch Company When the both of us get our new Stowas we should be able to see this really well! […]

henry

11 March, 2014 at 9:14 pm

fascinating, clear, and advanced advice. much better than anything i have come across at the Guildhall. thanks for taking the trouble to post it.

Colin

12 March, 2014 at 3:06 am

Thanks a lot for your comment Henry!

Joseph Bickley

26 April, 2014 at 8:43 am

Colin, thanks for putting this website together for us to read. You have put in lots of work. Extremely illuminating I have to say that. Have a great day!

—Joe

Colin

26 April, 2014 at 3:24 pm

Hi Joe, many thanks for your kind comments. Hopefully you found it useful

Adrian-T. Sofonea

20 November, 2014 at 3:30 pm

Really great idea.

minho

4 December, 2014 at 6:04 am

Hi Colin.

I am looking for the Duofix shock system used by Rolex.

Do you happen to know the shop url?

Merry Christmas Colin.

Colin

8 December, 2014 at 2:07 am

Hi Minho,

Rolex keep the supply of parts very tightly under their control, so you cannot buy anything officially Rolex related on the open market. Your best best would be to go through a Rolex accredited watch repairer who will be able to get the parts you need. They won’t be able to sell you the part themselves, as this is against their contract, but they would be able to fit it for you.

I hope that helps

Colin

minho

17 December, 2014 at 5:31 am

Thanks Colin

Merry Christmas and Happy New Year~~

dan cotton

8 December, 2015 at 5:25 pm

thanx for informative site Understand anti-shock systems a bit now!

Tom Zimmermann

22 January, 2016 at 1:03 pm

I’m a bit late to the party but this is very informative. Thank you! After studying this a bit I came across an article that claims Incabloc’s Novodiac is the ‘cheap’ model. Does this mean it protects less against damage, or lost time or both?

I am referring to Steinhart’s Ocean 1, which has this component.

Thank you

Colin

23 January, 2016 at 1:18 am

Hi Tom,

The Novodiac is much cheaper for ETA to produce, and is use mostly on their standard base calibres. Any movement with a high finish tends to still use the Incabloc setting.

Most watchmakers I know don’t like the Novodiac; and most wrongly call it a KIF spring. This is due to the removable nature of the spring which makes it awkward to take out and replace, and can also lead to it getting lost.

But function wise it is, theoretically at least, superior to the Incabloc setting. This is due to the fact that it has rotational symmetry and is secured in place equally at three points. The Incabloc had mirror symmetry and is secured at 4 points, although each point is not held down with an equal amount of force.

The difference is minimal though, and you’ll be hard pressed to break a balance staff pivot in a modern watch that uses any form of shock setting.

Colin

ThomasZimmermann

25 January, 2016 at 12:42 pm

Hello Colin

Thank you very much for taking the time to reply. I find myself researching more and more about watches and movements and will start buying soon, no doubt.

This could well become problematic as my other great passion, photography, also requires deep pockets…

Oh well, as long as I don’r start collecting cars * hehe*

Thanks again, Colin

Kind Regards

Tom

Roland

23 January, 2016 at 5:57 am

Hello Colin;

I’m also late to this thread but new to watches. With great interest I’m reading your very informative article. As my very first training watch, with the bar set high, I took a N.O.S. ETA 2540 (7-3/4 ligne) and totally stripped & rebuild it twice…….however, completely at the end, for oiling, I broke one leg of a hinge-type Incabloc spring 🙁

Curious what can be done, I started searching / learning (hindsight thing 🙂

Can just the hinge-spring be replaced, or do I need to replace the whole setting?

Maybe you could talk a bit about that and add to your article?

Thanks on beforehand !

Colin

24 January, 2016 at 11:26 pm

Hi Roland,

Shock springs are very easy to break and so occasionally you will have to replace them. For the Incabloc you can replace either the whole setting or just the spring.

To replace the entire setting you just need to get a watchmaker’s jewelling set and push the setting completely out and then replace it, remembering to depth it correctly afterwards.

To replace just the spring, you need the same set of tools. The spring is locked in place by the side of the bridge, and by raising the setting up slightly the spring will be released and the spring can be easily removemd and replaced.

Push the jewell from the underside of the setting up slightly, but not enough that it will come out. You should then be able to slide the old spring out, and you can then slide the new spring back in its place and close the spring. You then need to push the jewell setting back down, being careful to use the right tool to not damage the jewell or the spring, and not too big that it will bruise the bridge. You will then need to depth the jewell correctly.

The best way to depth a jewell is to see how it is set in the first place before you move it. Most jewells are set up so that they are naturally flush to the bridge/plate from either the top or the underside, and so you can get the rough depthing correct by duplicating this and then just make the extra micro adjustments as required.

I may take some photos the next time I do this, but it would also involve having to explain how to use the jewelling set; which is perhaps beyond the scope of the article.

I hope that helps.

Colin

Roland

25 January, 2016 at 6:16 am

Hello Colin;

Thank you very much for your elaborate reply!

I’ll put the watch aside as I haven’t got a watchmaker’s jewelling set. It was a training watch, N.O.S. for around £5 and doesn’t justify a jewelling set plus, I guess, I need to purchase a whole new incabloc. All a bit too much for a beginner I’m afraid. However the lesson(s) learned: I thought these springs were made out of a kind of spring-steel and could jump away. Concentration too much on holding it down with a peg-wood, I exercised too much force on one leg and broke it. It seemed to me “normal” brass and the “spring action” is obtained out of the “thinness”, combined with the length of the material. Next time I’ll be far more careful now I know, from your explanation, which model hinges, which are “jumpers” and what it all entails if you brake a spring.

If I were to brake another one, on a much more important watch, which does justifies a jewelling set, I’ll revisit this movement. Again as a trainer 😉

BTW: I found on YouTube a very nice video showing how to use a jewelling set and how to do a jewel change-out…….exactly as you described (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9fMTNuxDXmU)

Thanks again!

Roland.

John Paul Miranda

28 July, 2017 at 8:45 am

Thank you for the information.

Stephen Foskett

31 March, 2020 at 1:19 am

Thank you for this! I enjoyed the write-up and learned a great deal from it.

I would like to point out, however, that Swatch Group does not own Incabloc and never has. It was created by Portescap back in 1933 and spun out to become its own company in 1988. It remains independent today.

KIF has also been independent for decades, being a product of Parechoc of Le Sentier. Later renamed KIF-Parechoc, it was purchased by Acrotec in 2006 and remains part of that group.

Considering that ETA and Rolex rely on anti-shock of their own construction and design (Etachoc and Paraflex, respectively), this seems to be correct.

Colin

7 April, 2020 at 11:25 am

Hi Stephen,

Thank you for your comment and your clarification. I’ve updated the article.

Colin

Arno Jacobs

17 May, 2020 at 2:11 pm

My question is about the color of the bearing Jewels, normaly called rubies (whitch color is red by using some chromium in the corendum). Why is it that everyone say the bearing jewel of a wrist watch is color red but when I look at the bearing stones of wrist watches I see a purple color bearing stones, as I see also in the photo’s above (not the drawings). Are that still rubies?

Kind regards,

Arno

Blackie Ray

22 December, 2022 at 11:20 am

It’s 2022 -almost 2023 and I’ve just found your article. Clear, precise, and illuminating. So glad this is is here.

Thanks, Blackie